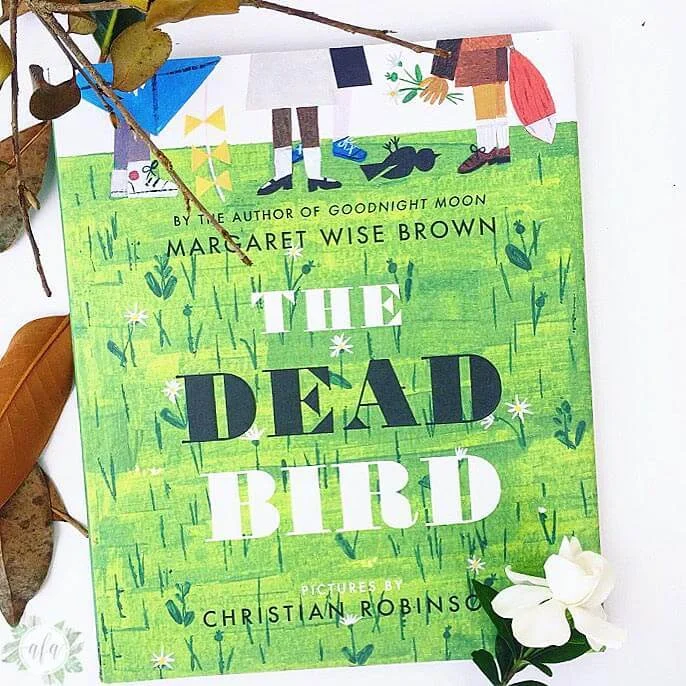

The Dead Bird

The Dead Bird, by Margaret Wise Brown, is stark and pointed. To the adult heart, with its existential concerns about meaning making, and its desire for sentiment, this book is startling. It opens: “The bird was dead when the children found it… there was no heart beating. That was how they knew it was dead.” Then later the children muse, “… That was the way animals got when they had been dead for some time – cold dead and stone still with no heart beating.”

After I read this book the first time, I reached out to friends and fellow book lovers, “How could this book be?” I complained. I had such high hopes; the art was so lively and lovely. I felt the text was plain and inconsiderate. Blinded by my own adult-ish needs for the dead to be warm in the great beyond, it was painful to read things like “cold” and “stiff” – descriptors Brown doesn’t bother to soften. But then I started thinking developmentally. I considered the concrete and literal nature of the 2-4 year old, and I realized that this book is actually, totally…brilliant. I started thinking that just maybe this book is the most considerate book that I have ever read. Here is why:

Children 2- 4 years old, don’t understand “forever.” For them, death is reversible, temporary, and impersonal. In fact, I learned working in psychiatric hospitals that children this age are a threat to “kill” something because they don’t understand the irreversibility of death at all. The Dead Bird takes this task head on. Without mincing words or introducing concepts for which the pre-school child does not yet have a framework, Brown stays grounded in the moment. This bird is dead, this bird is warm but will get cold, this bird is going in the ground. This bird will not come out of the ground. We forget this bird and go about our play, and the bird will still be there, in the ground, where we left it. The genius of this book is not in the way is simplifies expansive concepts, but in the way it sheds all of that to communicate one thing simply: Death is final. (It also gives permission to “play” at mourning, which is incredibly valuable, and I can get into that in another post).

Your pre-schooler will grow, and as her cognitive abilities allow, she will navigate and process other major death concepts like causality, inevitability, heartbreak, loss, and even emptiness. But for now, sweet guide sweet parent, be open and ready. Try and only answer the questions they ask, and answer them simply. Be patient. Children this age will likely ask over and over “when is (the deceased) coming home?” Depending on who you have lost, this can feel like a knife. My heart breaks for you. Be compassionate and consistent.

You can expect brief and intense reactions that will be ongoing as they accomplish new maturity levels. At this age, they are most concerned about separation and altered patterns of care. Find a way to be consistent and communicate that they will continue to be provided for (schedules, food, shelter, warmth). They are responsive to your emotional reactions and may compensate with acting out behavior. React to this less with punishment and more with reassurance: “I am okay, we are okay, everything is going to be okay, trust me.” Look for regression, sleep disruption, and reverting back to the use of an attachment object (paci, blanket, etc).

We think not talking about it will help our preschooler avoid the pain when in actuality is just causes them more worry. Be sensitive to your child, but my guess is that The Dead Bird will be helpful. I welcome (and hope for) your comments, questions, and ideas.